1

/

of

7

The Gently Mad Book Shop

The Richmond-Atkinson Papers (2 Vols) NEW ZEALAND Maori People / Early Settlers

The Richmond-Atkinson Papers (2 Vols) NEW ZEALAND Maori People / Early Settlers

Regular price

£70.00 GBP

Regular price

Sale price

£70.00 GBP

Unit price

/

per

Tax included.

Couldn't load pickup availability

The Richmond-Atkinson Papers

Edited by Guy H. Scholefield

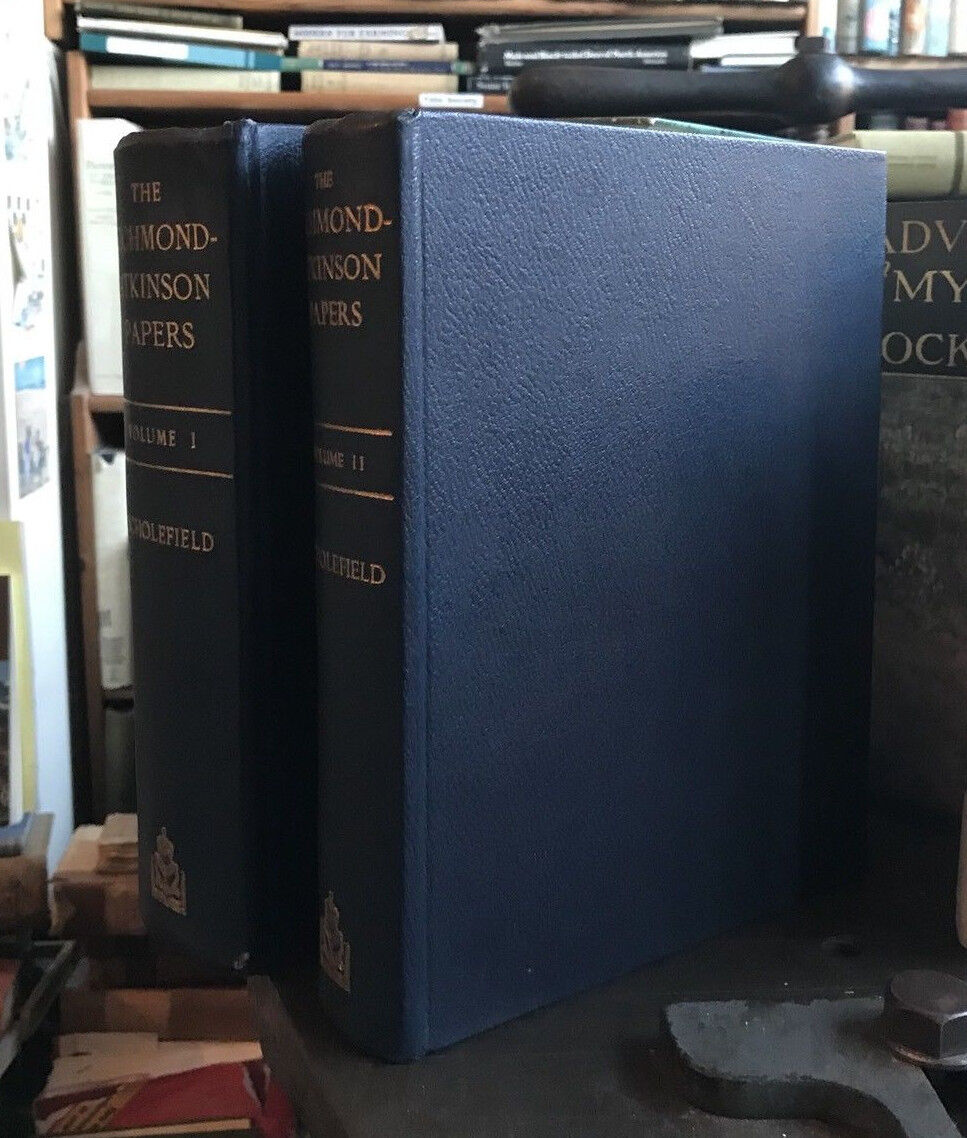

Published by R.E. Owen, Government Printer, Wellington, New Zealand, 1960. FIrst Edition. Complete in 2 volumes. Hardback, blue cloth, thick 4to, pp 853 + 658, illustrated.

CONDITION

Good clean condition throughout. Cloth bindings good. Pages clean throughout. These are NOT ex-library books and are in good clean condition.

FROM THE INTRO OF VOLUME I

History of the Collection

The survival for almost a century of the collection now known as the Richmond-Atkinson Papers was not a mere chance. It was due primarily to the congenital disposition of a family for recording and sporadic impulses towards conservation.

The Richmonds and Atkinsons and their relatives were a unique group of middle-class English men and women. Educated and cultured, many were efficient in the practical crafts of colonisation, and most showed an aptness for public service. Between 1843 and 1856 there was a movement of related groups from the Old World to the Antipodes which somewhat resembled the preparatory hekes of Maori communities from one district or island to another.

In the early days of this dispersal there was a lively interchange of news and impressions between the hemispheres, a simple family traffic. As the leaders of the colonists were drawn into public life their correspondence was broadened accordingly. Letter writing became more general and the instinct for documentation was unconsciously fostered. Thus the written memorials of this first generation embraced not only the rustic interests of bushfarmers but in succession the affairs of the township, the province, and the Colony at large. Before New Zealand was fifty years old these records were nationwide. Little indeed of our early history escaped the lively cognisance of these eager scribes.

The core of the collection may be said to reside in the letters and diaries of the five Richmonds and three Atkinsons and the diaries of Arthur S. Atkinson. There is in addition a mass of letters from political leaders and intellectuals all over New Zealand and abroad.

The Richmonds were superb letter writers: calligraphy and English were alike faultless. Maria Richmond (1791-1872), the matriarch of the emigrants, occasionally kept a journal, but she appears at her best in the letters of a woman of culture and discernment, interested in literature and philosophy and alert to current events. A counsellor of the new generation and a commentator on affairs, she shrewdly judged men and was a tolerant assessor of human motives. Some of her character sketches assist pleasantly to clothe with flesh and blood such historical figures as Alfred Domett and Sir Edward Stafford.

Maria Richmond's eldest son, (Christopher) William Richmond (1821-95), kept a fugitive diary at intervals in a busy life. His reflections and public acts are mainly to be found, however, in the archives of Government, Parliament, and the Supreme Court. Amongst his papers are some of an official character which would normally have come to rest in the National Archives if clerks had been available to relieve him of the double duty of writing the letters and keeping the records. Special value accordingly attaches to carbon copies of his correspondence in the fifties (vol 41) and a manuscript letter copybook (vol 42) covering spasmodically the periods 1854-59 and 1877. These may prove to contain the sole record of certain exchanges between Richmond as Colonial Secretary and the Governor (Col. T. Gore Browne) in the crisis of the Taranaki war and in the establishment of responsible government. In later life, when he was more congenially employed as a judge, Richmond was often engaged by fellow intellectuals in debating such topics as materialism, Christian socialism, religion, and social reform. Many of his speeches and lectures and addresses to the jury were published in England and in the Colony. His swift clear hand, despite the frequency of legal abbreviations, left nothing obscure in his meaning.

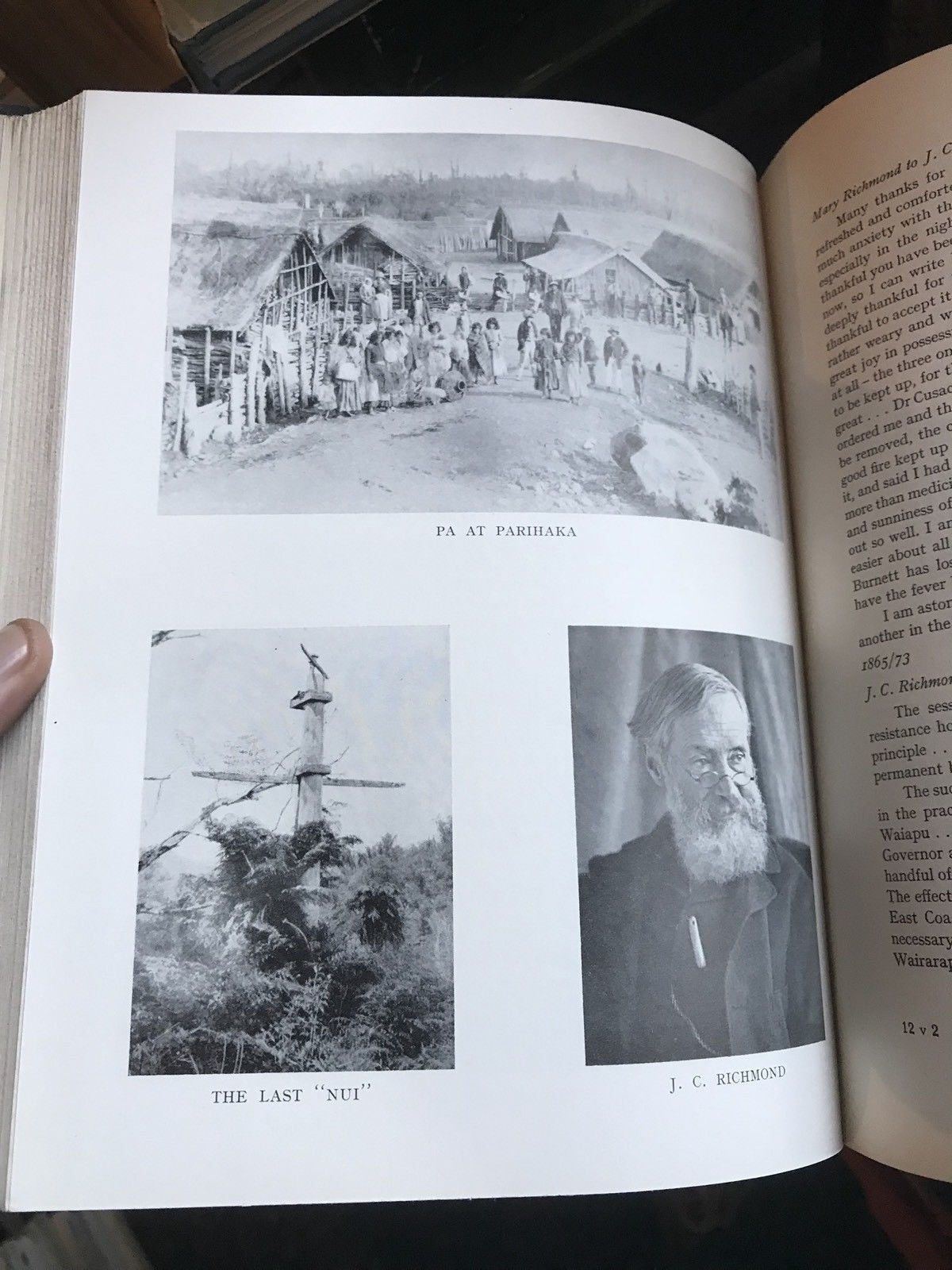

The second son, James Crowe Richmond (1822-98), later recognised as one of New Zealand's most talented artists, is strongly represented also as engineer, journalist, free-thinking philosopher, and administrator. He wrote in a swift copperplate hand. There are some letters too by his wife, Mary Smith (1834-65), whose courtship is commemorated in a striking series. Of their artist daughter, Dorothy K. Richmond, there are some letters.

The youngest of the Richmond sons, Henry R. Richmond (1829-90), had a strong bent for physical science and essayed some forward-looking theories hinting at the atomic age. Shrinking from public life, he corresponded with scientists oversea with a sturdy wistful curiosity.

Running throughout the collection like a continuous thread are the letters and diaries of Jane Maria Richmond (1824-1914), whose marriage to Arthur Atkinson reinforced the union of the families and strengthened their influence on the New Zealand tradition. Her education specialised in literature, music, and art. Warmhearted and outspoken, she was eminently practical and possessed an Amazonian spirit that shirked no dilemma and flinched at no aspect of physical danger. Arthur Atkinson (1833-1902) was several years her junior and the best educated of the Atkinsons. He was devoted to the classics and philology, poetry and the study of nature. Even in the Richmond circle he is distinguished for his patiently polished letters and his excellent journals. A painstaking, methodical recorder, each day for a quarter of a century he noted not only local events - exciting or humdrum as the case might be - but also his own dip into the classics, his observations on birds, the stars and the weather, or some new Maori idiom or legend. In him poesy and scholarship flourished about the hard core of endeavour and duty.

Jane Maria and her husband were passionate champions of the tortured province in which their lot was cast. In its defence they yielded to the hot temper of politics and bitterly attacked the general government, even when William Richmond happened to be a member of it. Inevitably in those days of isolation and remoteness public feeling was at the mercy of rumour and gossip. In common with their friends Mr and Mrs Atkinson occasionally gave currency to the sort of scandal that such primitive circumstances engendered. This is not surprising, for political partisanship was nothing new to men and women who had lived in England in the forties.

[Image of page 7]

Generally speaking, mere gossipy passages have not been considered worthy of reproducing in this publication. If the question is asked: Why give them at all? the answer is that such trivia, committed to writing by men and women of education and social standing, afford evidence of the background or climate in which our grandfathers lived. To ignore them would rob the chronicle of a measure of human warmth that must be helpful in interpreting the times.

Harry A. Atkinson (1831-92) was essentially a man of action. The diary that he kept now and again was only for farm purposes. His writing, though quite without style, is never obscure. The. intimate correspondence of the two Atkinson brothers during the later decades of Sir Harry's life documents with peculiar authority the political background of the period and stands high as source material.

The letters of these half dozen or so members of the two families maintain a substantial thread of history through the collection. There are, in addition, many hundreds of letters from thinkers and men of action in the Colony and beyond.

Arthur Ponsonby, surveying the material at hand for the life of his father, reflected on the family habits of keeping or destroying letters:

There may be no particular intention or merit in either practice but posterity is grateful to those who do not destroy their papers, because ... a number of letters describing the day's doings, referring to unknown people or recording trivial events have the cumulative effect of giving the atmosphere, domestic or professional, and revealing the character, the disposition, and even the passing moods of the writer. 1

Amongst the Richmond-Atkinson group were many correspondents who are easily recognisable as "keepers and not destroyers". The keeping impulse was awakened early amongst the colonists by the controversy over the Taranaki war. In 1860 - for the first time in history, we are told - British volunteers were in action in a military campaign. The Taranaki volunteers at Waireka were not adequately supported by the British military commanders and unhappy recrimination ensued between settlers and soldiers. To satisfy the curiosity of William Richmond (who was in Auckland) and to ensure that the conduct of the volunteers would be rightly appraised, the two Atkinsons and the Ronalds brothers wrote separate narratives of their experiences in the engagement.

A year or two later the Atkinsons were urged by James Edward FitzGerald to write a history of the war. Another crisis pushed the project aside but the recording passion did not languish. At the time of the migration (in 1852) Jane Maria Richmond made a compact with a school friend (Margaret Taylor) to correspond continuously, each to preserve the letters of the other. Jane Maria maintained this interchange for years, her letters being addressed in the first instance to Miss Mary Elizabeth Hutton, to be read by the English circle before going on to Margaret Taylor in Germany.

[Image of page 8]

Shortly after Sir Harry Atkinson's death (in 1892) the family considered publishing his biography, and Arthur and Jane Maria set to work methodically to gather documentary material covering the first fifty years of the Colony. An imposing quantity was already in their hands. The writing of the life was entrusted in the first instance to Maurice Richmond, who was practising law in Wellington, and he had made some progress in arranging the material until 1900 when he was appointed a lecturer at Victoria University College. In 1902 Arthur Atkinson died, leaving behind a respectable body of material which had been carefully annotated by himself, and by Maurice Richmond, Mrs C. W. Richmond, and others. The next author proposed was Sir Harry's son, S. A. Atkinson. 2 He added something to the documentation and made a short draft for the life, which then hung fire for a while.

At this stage it was proposed that Miss Margaret Shaen 3 should finish the task and she took to England a quantity of the relevant papers. When her effort fell through the papers were returned to New Zealand and on the death of Jane Maria Atkinson (in 1914) they became the care of her daughters Ruth and Mabel. 4 The former had in 1911 informed Miss Shaen that "all of Margaret Taylor's letters were saved for us by Maggie Cobden". 5 This refers presumably to Jane Maria's own letters, some of which have found their way to the collection: others which have not been traced were evidently available in 1931. Margaret Taylor's own letters and those between A. S. Atkinson and his wife and between him and their son (A. R. Atkinson) have not been located.

About 1930 Miss Mary E. Richmond, C.B.E. (1853-1949), and Miss Emily Richmond (1869-1950), the surviving daughters of C. W. Richmond, made a compilation from the letters, partly for the information of the family and partly as historical source material. This was typed by Mr A. H. Reed, M.B.E., of Dunedin and bound in two volumes, copies being deposited in several research libraries in New Zealand. (Those in the General Assembly Library are cited here as vols 38 and 39). It was then that the Misses Richmond intimated to the present editor (who was chief librarian of the General Assembly Library), their intention of presenting the papers as a gift to the nation. The gift was gratefully acknowledged by the Library Committee of Parliament.

Edited by Guy H. Scholefield

Published by R.E. Owen, Government Printer, Wellington, New Zealand, 1960. FIrst Edition. Complete in 2 volumes. Hardback, blue cloth, thick 4to, pp 853 + 658, illustrated.

CONDITION

Good clean condition throughout. Cloth bindings good. Pages clean throughout. These are NOT ex-library books and are in good clean condition.

FROM THE INTRO OF VOLUME I

History of the Collection

The survival for almost a century of the collection now known as the Richmond-Atkinson Papers was not a mere chance. It was due primarily to the congenital disposition of a family for recording and sporadic impulses towards conservation.

The Richmonds and Atkinsons and their relatives were a unique group of middle-class English men and women. Educated and cultured, many were efficient in the practical crafts of colonisation, and most showed an aptness for public service. Between 1843 and 1856 there was a movement of related groups from the Old World to the Antipodes which somewhat resembled the preparatory hekes of Maori communities from one district or island to another.

In the early days of this dispersal there was a lively interchange of news and impressions between the hemispheres, a simple family traffic. As the leaders of the colonists were drawn into public life their correspondence was broadened accordingly. Letter writing became more general and the instinct for documentation was unconsciously fostered. Thus the written memorials of this first generation embraced not only the rustic interests of bushfarmers but in succession the affairs of the township, the province, and the Colony at large. Before New Zealand was fifty years old these records were nationwide. Little indeed of our early history escaped the lively cognisance of these eager scribes.

The core of the collection may be said to reside in the letters and diaries of the five Richmonds and three Atkinsons and the diaries of Arthur S. Atkinson. There is in addition a mass of letters from political leaders and intellectuals all over New Zealand and abroad.

The Richmonds were superb letter writers: calligraphy and English were alike faultless. Maria Richmond (1791-1872), the matriarch of the emigrants, occasionally kept a journal, but she appears at her best in the letters of a woman of culture and discernment, interested in literature and philosophy and alert to current events. A counsellor of the new generation and a commentator on affairs, she shrewdly judged men and was a tolerant assessor of human motives. Some of her character sketches assist pleasantly to clothe with flesh and blood such historical figures as Alfred Domett and Sir Edward Stafford.

Maria Richmond's eldest son, (Christopher) William Richmond (1821-95), kept a fugitive diary at intervals in a busy life. His reflections and public acts are mainly to be found, however, in the archives of Government, Parliament, and the Supreme Court. Amongst his papers are some of an official character which would normally have come to rest in the National Archives if clerks had been available to relieve him of the double duty of writing the letters and keeping the records. Special value accordingly attaches to carbon copies of his correspondence in the fifties (vol 41) and a manuscript letter copybook (vol 42) covering spasmodically the periods 1854-59 and 1877. These may prove to contain the sole record of certain exchanges between Richmond as Colonial Secretary and the Governor (Col. T. Gore Browne) in the crisis of the Taranaki war and in the establishment of responsible government. In later life, when he was more congenially employed as a judge, Richmond was often engaged by fellow intellectuals in debating such topics as materialism, Christian socialism, religion, and social reform. Many of his speeches and lectures and addresses to the jury were published in England and in the Colony. His swift clear hand, despite the frequency of legal abbreviations, left nothing obscure in his meaning.

The second son, James Crowe Richmond (1822-98), later recognised as one of New Zealand's most talented artists, is strongly represented also as engineer, journalist, free-thinking philosopher, and administrator. He wrote in a swift copperplate hand. There are some letters too by his wife, Mary Smith (1834-65), whose courtship is commemorated in a striking series. Of their artist daughter, Dorothy K. Richmond, there are some letters.

The youngest of the Richmond sons, Henry R. Richmond (1829-90), had a strong bent for physical science and essayed some forward-looking theories hinting at the atomic age. Shrinking from public life, he corresponded with scientists oversea with a sturdy wistful curiosity.

Running throughout the collection like a continuous thread are the letters and diaries of Jane Maria Richmond (1824-1914), whose marriage to Arthur Atkinson reinforced the union of the families and strengthened their influence on the New Zealand tradition. Her education specialised in literature, music, and art. Warmhearted and outspoken, she was eminently practical and possessed an Amazonian spirit that shirked no dilemma and flinched at no aspect of physical danger. Arthur Atkinson (1833-1902) was several years her junior and the best educated of the Atkinsons. He was devoted to the classics and philology, poetry and the study of nature. Even in the Richmond circle he is distinguished for his patiently polished letters and his excellent journals. A painstaking, methodical recorder, each day for a quarter of a century he noted not only local events - exciting or humdrum as the case might be - but also his own dip into the classics, his observations on birds, the stars and the weather, or some new Maori idiom or legend. In him poesy and scholarship flourished about the hard core of endeavour and duty.

Jane Maria and her husband were passionate champions of the tortured province in which their lot was cast. In its defence they yielded to the hot temper of politics and bitterly attacked the general government, even when William Richmond happened to be a member of it. Inevitably in those days of isolation and remoteness public feeling was at the mercy of rumour and gossip. In common with their friends Mr and Mrs Atkinson occasionally gave currency to the sort of scandal that such primitive circumstances engendered. This is not surprising, for political partisanship was nothing new to men and women who had lived in England in the forties.

[Image of page 7]

Generally speaking, mere gossipy passages have not been considered worthy of reproducing in this publication. If the question is asked: Why give them at all? the answer is that such trivia, committed to writing by men and women of education and social standing, afford evidence of the background or climate in which our grandfathers lived. To ignore them would rob the chronicle of a measure of human warmth that must be helpful in interpreting the times.

Harry A. Atkinson (1831-92) was essentially a man of action. The diary that he kept now and again was only for farm purposes. His writing, though quite without style, is never obscure. The. intimate correspondence of the two Atkinson brothers during the later decades of Sir Harry's life documents with peculiar authority the political background of the period and stands high as source material.

The letters of these half dozen or so members of the two families maintain a substantial thread of history through the collection. There are, in addition, many hundreds of letters from thinkers and men of action in the Colony and beyond.

Arthur Ponsonby, surveying the material at hand for the life of his father, reflected on the family habits of keeping or destroying letters:

There may be no particular intention or merit in either practice but posterity is grateful to those who do not destroy their papers, because ... a number of letters describing the day's doings, referring to unknown people or recording trivial events have the cumulative effect of giving the atmosphere, domestic or professional, and revealing the character, the disposition, and even the passing moods of the writer. 1

Amongst the Richmond-Atkinson group were many correspondents who are easily recognisable as "keepers and not destroyers". The keeping impulse was awakened early amongst the colonists by the controversy over the Taranaki war. In 1860 - for the first time in history, we are told - British volunteers were in action in a military campaign. The Taranaki volunteers at Waireka were not adequately supported by the British military commanders and unhappy recrimination ensued between settlers and soldiers. To satisfy the curiosity of William Richmond (who was in Auckland) and to ensure that the conduct of the volunteers would be rightly appraised, the two Atkinsons and the Ronalds brothers wrote separate narratives of their experiences in the engagement.

A year or two later the Atkinsons were urged by James Edward FitzGerald to write a history of the war. Another crisis pushed the project aside but the recording passion did not languish. At the time of the migration (in 1852) Jane Maria Richmond made a compact with a school friend (Margaret Taylor) to correspond continuously, each to preserve the letters of the other. Jane Maria maintained this interchange for years, her letters being addressed in the first instance to Miss Mary Elizabeth Hutton, to be read by the English circle before going on to Margaret Taylor in Germany.

[Image of page 8]

Shortly after Sir Harry Atkinson's death (in 1892) the family considered publishing his biography, and Arthur and Jane Maria set to work methodically to gather documentary material covering the first fifty years of the Colony. An imposing quantity was already in their hands. The writing of the life was entrusted in the first instance to Maurice Richmond, who was practising law in Wellington, and he had made some progress in arranging the material until 1900 when he was appointed a lecturer at Victoria University College. In 1902 Arthur Atkinson died, leaving behind a respectable body of material which had been carefully annotated by himself, and by Maurice Richmond, Mrs C. W. Richmond, and others. The next author proposed was Sir Harry's son, S. A. Atkinson. 2 He added something to the documentation and made a short draft for the life, which then hung fire for a while.

At this stage it was proposed that Miss Margaret Shaen 3 should finish the task and she took to England a quantity of the relevant papers. When her effort fell through the papers were returned to New Zealand and on the death of Jane Maria Atkinson (in 1914) they became the care of her daughters Ruth and Mabel. 4 The former had in 1911 informed Miss Shaen that "all of Margaret Taylor's letters were saved for us by Maggie Cobden". 5 This refers presumably to Jane Maria's own letters, some of which have found their way to the collection: others which have not been traced were evidently available in 1931. Margaret Taylor's own letters and those between A. S. Atkinson and his wife and between him and their son (A. R. Atkinson) have not been located.

About 1930 Miss Mary E. Richmond, C.B.E. (1853-1949), and Miss Emily Richmond (1869-1950), the surviving daughters of C. W. Richmond, made a compilation from the letters, partly for the information of the family and partly as historical source material. This was typed by Mr A. H. Reed, M.B.E., of Dunedin and bound in two volumes, copies being deposited in several research libraries in New Zealand. (Those in the General Assembly Library are cited here as vols 38 and 39). It was then that the Misses Richmond intimated to the present editor (who was chief librarian of the General Assembly Library), their intention of presenting the papers as a gift to the nation. The gift was gratefully acknowledged by the Library Committee of Parliament.

(Storage)

Share with someone